Make your vote count for mental health in the upcoming election

Written by Clinical Psychologist Aaron Frost

In a little over two weeks, Australia heads to the polls to elect a new Federal parliament. There are a lot of issues in play, but for those of you interested in mental health we have a guide of what the big issues are, and where each party stands on each. Before looking at the politics, let’s start by outlining the key issues.- Australia’s suicide rate has recently spiked upward

- There is a bed shortage for patients with acute and severe mental health conditions

- People in rural and remote areas, low socioeconomic areas and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have low rates of access to treatment

- The burden of disease for mental illness represents around 4% of GDP

- Almost half of our mental health spending is “downstream”, ie: for dealing with the consequences of poor mental health (homelessness, welfare, criminal justice etc).

- Australia’s “spend” on mental health is low by OECD standards

Good policy would be:Have some plan to reduce suicide rates

- Increase mental health beds for patients with acute and severe conditions

- Increase access to disadvantaged groups (rural and remote, low SES, Indigenous Australians)

- Look to reduce the burden of disease by increasing treatment availability and effectiveness

- Currently there are a number of existing programs that receive the majority of funding in order to achieve the above goals. No party appears to be committing to any out of the box overhaul of these systems or any significant funding increases, so therefore it is useful to consider what these programs are and where they fit into the picture.

National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) - exists to provide long-term inclusive support for people with permanent disabilities. While many people with mental illnesses make full or partial recoveries, permanent disability is exactly how the needs of many should be viewed. However, currently the NDIS appears to have a poor understanding of mental health issues, and a general fear of opening up the program to mental illness as it risks blowing out an already stretched budget.

↣ Needs - Directing some additional funding into the NDIS to deal with psychosocial disability is almost a prerequisite of good policy.

Primary Health Networks (PHNs) - were developed to allow regional differentiation in health coordination, on the assumption that the needs of one area may be different from the needs of another. While the PHNs do not provide treatment directly, they do receive substantial funding, which they can then use to purchase treatment services based on the needs of their local community. While decentralisation has been a huge step forward in terms of regional differentiation, significant questions have been raised about the capacity of all of these regional boards to develop competent financial and clinical governance. Large administrative overheads, both for the PHNs and then the agencies they tender work out to is proving to cost more and deliver less to treatment.

↣ Needs - Good policy in this space would probably see a commitment to improved governance for the PHNs (simply rebranding them from Medicare Locals is not enough). Additional resources directed to the PHNs without such improved governance risks achieving very little other than blowing out a bureaucracy.

Headspace - Strives to increase access for youth. Their accessible centres are designed to be youth friendly and inclusive. They have been modelled on the centre for excellence in youth mental health treatment in Parkville Victoria (Orygen). However, recent evaluations have suggested that Headspace has struggled to “scale up”, meaning that while some of their centres are providing excellent services, many of them are underperforming, and outcomes have been underwhelming.

↣ Needs - Headspace funding needs to be assured. The short-term funding arrangements that have defined its recent history are damaging to long term sustainability. However, Headspace also needs support in delivering on its promise. Simply examping the model does not address the underlying problems.

Better Access - This is the program introduced in 2006 whereby GPs can refer directly to psychological treatment services and clients can receive a medicare rebate. This program has been a huge success in terms of increasing patient access (almost doubling over ten years), however the only evaluation done on this program in 2011 was very limited in scope and does not really provide assurance that increased access has led to increased outcomes. A recent review by Lee & Frost published in MJA found that Better Access had reduced the rates of those suffering high levels of psychological distress, but that the session cap introduced in 2011 had decreased the program effectiveness. This article can be accessed here.

↣ Needs - Better Access needs session limits increased or scrapped. There is no evidence that increasing session limits would cost more money as the workforce is stable (there are no additional psychologists left to do additional work), and increased session limits would allow this program to deliver support to clients with greater needs without risking their mental health by treatment disruption. At the same time, money needs to be invested in the evaluation of this program.

Web based platforms - There are a number of hubs that have formed nationally whereby organisations have been funded to collate apps, websites, phone counselling services and other treatment that can be delivered at almost zero cost. These programs are understandably popular, both for their ongoing running costs, as well as their ability to reach people in regional and remote areas such as a teen who might be 100km away from the nearest GP, let alone a psychiatrist or psychologist. However, web based platforms have yet to crack the drop-out problem, with research suggesting that in some programs as many as 90% of people do not return after their first interaction with the website.

Web based platforms - There are a number of hubs that have formed nationally whereby organisations have been funded to collate apps, websites, phone counselling services and other treatment that can be delivered at almost zero cost. These programs are understandably popular, both for their ongoing running costs, as well as their ability to reach people in regional and remote areas such as a teen who might be 100km away from the nearest GP, let alone a psychiatrist or psychologist. However, web based platforms have yet to crack the drop-out problem, with research suggesting that in some programs as many as 90% of people do not return after their first interaction with the website.

↣ Needs - More funding dedicated to basic research. These programs are promising, and will definitely have a place in the treatment mix of the future. However, until the dropout problem is improved markedly they are not yet ready to be considered frontline treatment resources.

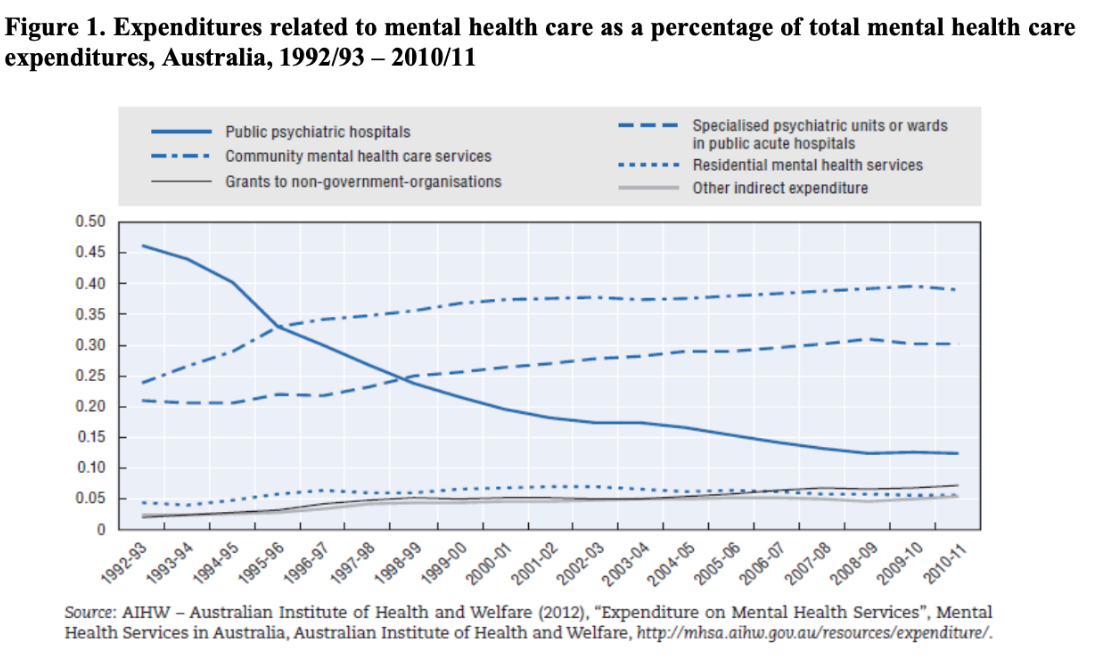

Public Hospitals - As the graph below shows, in 1992 public psychiatric facilities used to make up 46% of total mental health spending, but it has dropped and has been relatively stable at around 12% since 2010. Australia now has 39 psychiatric beds per 100,000 of population, compared to an OECD average of 68. No one is calling for a return to the bad old days of the asylum, but perhaps there is a bit of wiggle room between 39:100,000 and 68:100,000 to add a few more beds around the place. However this is expensive, both in terms of capital expense and in terms of running these facilities. Big dollars require state and federal co-operation, which has been in pretty short supply in my observation of COAG meetings.